Lucan: Civil War

Reflections on Caesar, Pompey, and Cato

Why did Brutus decide to murder Caesar? He, and his co-conspirators, had a lot to gain by keeping the dictator alive. The benefits of Caesar’s rule were obvious: unimaginable wealth for the senatorial elite, opportunities for advancement among equestrians and provincial worthies, and stability and peace for all Romans after multiple civil wars. By contrast, the drawbacks of Caesar’s continued existence weren’t so apparent. It’s easy to fall back on abstract notions of “liberty”—as the “Liberators” did by labeling themselves as such—and claim that Caesar, a “tyrant,” suppressed the freedoms owed to the senators as Roman men. But that assertion isn’t entirely fair. The Senate continued to meet and debate (albeit with some new, Caesar-approved members), and Caesar’s position as dictator wasn’t anything unusual (apart from his lifetime term). The dictator himself was magnanimous, genuinely forgiving many of the men who fought against him in a civil war that he did not instigate, and continuing to value their counsel and friendship. What’s not to like?

Caesar’s clemency provides a hint at what really pushed Brutus to violence. Forgiving a proud man is a dangerous game. Instead of producing gratitude, it is likely—perhaps even certain—to generate resentment. Over time, that resentment can mutate into envy, and even hatred, of the forgiving man, and the power that allowed him to be forgiving.

Brutus, and many of his co-conspirators, were afflicted by this emotional malaise. They came to hate Caesar for his status as the BEST Roman. In defeating the Gauls, vanquishing Pompey, and becoming dictator, Caesar acquired more glory than any Roman who had ever lived. The terms of his political settlement ensured that no Roman would ever usurp his status. In so doing, he denied the Roman elite the ability to pursue the ways of their ancestors: to compete amongst each other, in a never-ending quest for status and honor, for both them and Rome. In other words, Caesar denied his erstwhile peers the ability to BE Roman. When viewed in this way, it is not at all shocking that Brutus & Co. murdered Caesar—and thought it just and right to do so.

Of course, things didn’t work out for them. After murdering Caesar in spectacular fashion, the Liberators lost the subsequent civil war in equally spectacular fashion. Augustus, the ultimate victor of that war, created the monarchy that ruled Rome, in one form or another, for almost 500 years thereafter.

But the republican sentiment that led to Caesar’s assassination — that, in eliminating the freedom of the senatorial elite to compete with and outshine him, he had destroyed the essence of Rome and being Roman — endured long after Augustus. This spirit animates Civil War, an epic poem written by Lucan during Nero’s reign in the 60s AD. In this post, I’ll give some background on Lucan, his influence on later writers, and then discuss three thematic elements of the book that I found interesting—and hope you will too! 1

Lucan

Lucan was born in Hispania in 39 AD, to a wealthy family with connections in Rome. He was educated in Athens and probably received instruction from his uncle, the Stoic philosopher Senaca. Senaca also tutored the Emperor Nero, with whom Lucan became close friends. His friendship with the emperor gave him access to politics—Nero made him quaestor, despite Lucan being under the age requirement—and also an outlet for his artistic abilities, as he wrote poetry with Nero’s patronage. Despite their close relationship, Lucan and Nero fell out sometime in the 60s AD, perhaps due to political disagreements or Nero’s jealousy of Lucan’s talents.

During this time, Lucan wrote Civil War, also known as Pharsalus. The poem depicts what is now referred to as Caesar’s Civil War, which occurred in the late 40s BC. The Senate, through a legally dubious decree, ordered Caesar to relinquish his command in Gaul and return to Rome as a private citizen. Had Caesar done so, he would have faced certain prosecution and possible death, for illegal extension of and public corruption related to his campaign in Gaul.

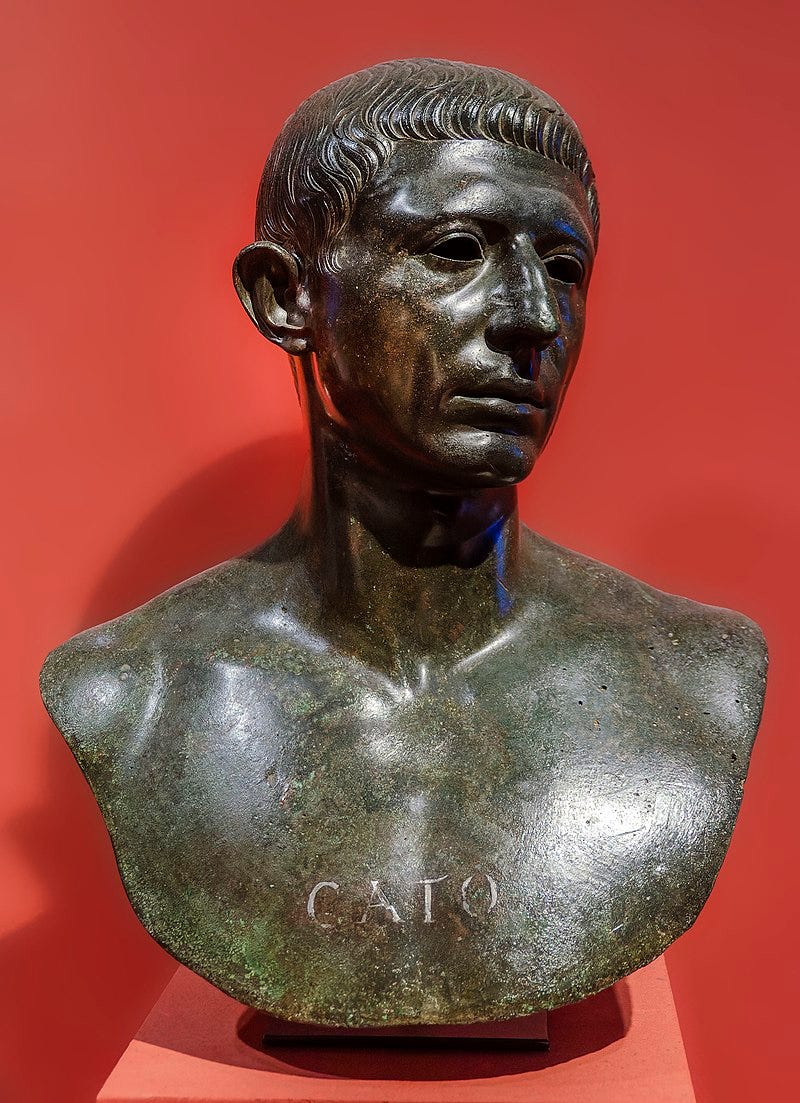

Caesar refused the Senate’s order. Now an outlaw, he crossed the Rubicon with a single legion, and marched on Rome. The Senate, led by, among others, Pompey the Great and Cato the Younger, fled the city and regrouped in Greece, where they rallied a number of legions and other troops from client kingdoms in the East. Caesar followed them across the Adriatic and destroyed their army at Pharsalus.

Pompey, now bereft of an army, sailed to Egypt, where he hoped to align with the Ptolemies, with whom he had had good relations during his prior campaigns in the East. The young king, Ptolemy XIII, had other ideas—and had Pompey murdered as he walked ashore in Alexandria. Ptolemy, embroiled in a civil war with his sister Cleopatra, believed assassinating Pompey would win him Caesar’s support. He guessed wrong. Caesar, outraged that a foreign king would dare murder a Roman consul, allied with Cleopatra, defeated Ptolemy’s armies, and caused his death.

Meanwhile, Cato fled Pharsalus for Africa, where he raised additional troops. After settling Roman affairs in Egypt, Caesar moved his forces to Africa, and defeated Cato at Utica. Cato committed suicide soon after. Caesar returned to Rome, where he was appointed dictator for life in 49 BC.

Civil War, ironically dedicated to Nero, is an openly partisan work. Cato is the hero of the poem. Pompey is fulsomely praised, while Caesar is regularly denigrated. Lucan also has no patience for Caesar’s cause—he labels Caesar’s march on Rome a “crime,” and laments that his actions have been made “law” by the subsequent regime of his heirs. For Lucan, that regime also snuffed out ancient Roman liberties and freedoms, which Cato epitomized and sought to defend. While Lucan probably intended to end the poem with Cato’s suicide in Utica, the book abruptly ends with Caesar fighting Ptolemaic forces in Alexandira.

The poem’s unfinished state is due to Lucan’s untimely death. In 65 AD, Lucan joined a conspiracy to overthrow Nero. When Nero discovered his erstwhile friend’s role in the plot, he forced him to commit suicide. Lucan was 25 years old.2

While Civil War is not considered one of the A-list Latin works—it is not as well written as the Aeneid or Metamorphosis—it has influenced a number of subsequent artists. Dante explicitly references the witch Erictho, one of the more memorable characters in Civil War, in the Divine Comedy. Milton’s frequent references to Lucretius in Paradise Lost also suggest Lucan’s influence, as Civil War’s discussion of Fate and Fortune is direct reference to Lucretius and Epicurean philosophy. Milton’s depiction of Satan also echoes certain aspects of Lucan’s depiction of Caesar (though antagonists, both dominate the epics; Lucan refers to Caesar as a “morning star,” as does Milton with Satan by referencing his former name, “Lucifer”). Closer to home, Moses Ezekiel, a Confederate veteran who designed the Confederate Memorial at the national cemetery in Arlington, inscribed the following line from Civil War on the Memorial:

VICTRIX CAUSA DIIS PLAUCIT SED VICTA CATONI

The Gods favored the victor, but Cato the lost cause.

The Biden administration ordered the Memorial removed from the cemetery in December 2023.

With that background in mind, let’s look at three themes from the poem: Caesar and his character, the depiction of Pompey and Cato, and Lucan’s moralizing.

Caesar

As noted, Lucan doesn’t like Caesar. He depicts him as rash (“reckless in everything”), bloodthirsty (“raving for battle, enjoys no way of passage unless blood is shed”), and insane (“[Caesar] is out of his mind!”). Lucan characterizes Caesar as having no self-control—he participates in foreign rites and a gluttonous banquet with Cleopatra—a quality shared by another tyrant, Alexander, whose path Caesar obsessively tracks as he pursues Pompey throughout the East.

Throughout the poem, Lucan associates Caesar with a bolt of lightning, or a morning star, bringing fire, mayhem, and destruction in his wake. His defining quality is his limitless ambition: “this man for whom the span of the entire Roman world is not enough, who thinks that a kingdom from Tyrian Gades to India would be small[.]” The Roman system cannot contain Caesar, and he levels everything in his path. When his will is challenged by the Senate and the law, he sets out to destroy the Senate and the law. Caesar’s supposed personal failings contrast with the virtues of Pompey (in Lucan’s telling) and Cato.

The thing is—are Caesar’s personal failings actually failings? A bolt of lightning is awesome (in the original and modern sense). Caesar’s ambition can also be reframed in a positive light: he has a desire for excellence, and a WILL to overcome every obstacle to be the preeminent man in Rome.

More important: was Caesar wrong to march on Rome? He did so because Cato—recklessly—convinced the Senate to strip him of his command. In the process, Cato—illegally!—suppressed the veto of a Caesarian Tribune to force through the motion. This is not to say that all of Caesar’s actions were legally correct. But Cato’s all-consuming—one might say irrational—hatred and fear of Caesar, and the supposed “tyranny” he sought to institute, suggests that ultimate culpability for the civil war can be ascribed to Cato, not Caesar.

When read in light of this historical background, which makes his praise of Cato and Pompey ring somewhat hollow, Lucan’s depiction of Caesar undermines the political agenda of the poem. Caesar is the most compelling character in Civil War. When he is present, the poem is energetic, powerful, and, well, epic. When he is not, it drags. Here is Lucan’s imagining of Caesar at the Rubicon:

Caesar, once he has touched the opposite bank of the river he has subjected, speaks out where he stands in Hesperia’s forbidden fields:

“Here, right here, I shed peace and our defiled laws. Fortune, I follow you. Faith can go to the winds—I’ve put my trust in the Fates. Let war decide!”

So declaring, in night’s darkness the rapid general drives his army, like stones from Balearic slings, swifter than a retreating Parthian shooting arrows, he swoops to invade nearby Ariminum, while stars flee the sun’s flame, leaving the morning star.

Caesar addresses his mutinous troops:

He stood on a pile of heaped-up sod, his gaze unshaken, inspiring fear, fearless himself, his rage dictating this speech:

“I wasn’t here to see your fists and faces raging, soldiers! Here’s my chest, barred and ready for wounds! If it’s end to war you want, leave swords here and flee. This cowardly sedition has dared nothing, except to expose your souls as unfit for war! Just a bunch of boys with dreams of flight, tired of successes and an undefeated leader. Go! And leave the wars and me to my fates. These weapons will find hands. As for you rejects, Fortune will supply enough men to take your spears . . . don’t you think Victory will give me a crowd to take the prizes she offers as wages for your labor in this all-but-routed war and escort unwounded my chariot decked in laurels? While you’ll be bloodless old men just watching our triumphs, part of the Roman rabble, despised. You think Caesar’s onward march would even notice your desertion?”

…

“You really think your efforts for me have ever carried weight? The gods don’t care, they’d never stoop so low, the Fates don’t give a damn about your life or death. Everything follows the whims of men of action. Mankind lives for the few.”

…

“Now, I’ll wage the wars for myself. Get out of camp! Pass my standards to men, you spineless civilians. You few responsible for this raving madness—your punishment, not Caesar, detains you here. Lie down on the ground and stretch your faithless heads and necks out for the death blow. And you, who now stand as the camp’s last strength, you raw recruits, observe these executions and learn both how to kill and how to die.”

Needless to say, he suppressed the mutiny.

It’s possible that Lucan’s treatment of Caesar is ambiguous. In depicting Caesar as alluring—so much so that he has overwhelmed even a hostile author—Lucan may be trying to warn the reader of the dangers of willful and charismatic men. But Lucan’s frequent condemnation and denigration of Caesar suggests against this more nuanced interpretation. He hates Caesar, and means what he says. Like modern artists who set out to condemn war, only to end up glorifying it, Lucan tried to write a poem condemning Caesar, only to make him its hero.

Pompey and Cato

The intended heroes of Civil War are Cato, and to a lesser extent, Pompey. Cato and Pompey, Lucan says, exhibit the classic virtues of the Republic and Romans of old: self-control, asceticism and disdain for luxury, and subordination of private desire to the public good. Whether this is true is debatable and Lucan’s case isn’t very convincing.

We’ll start with Pompey. In contrast to Caesar’s lightning bolt, Pompey is beautifully compared to an oak tree:

He stands in his great name’s shadow. Like a mighty oak in a bountiful field, weighed down with a people’s old war spoils and gifts by devoted leaders, its strong roots no longer holding it, just its sheer fixed mass, spreading its naked branches through the air, its trunk and not its boughs now casting shadow. And though it nods, about to fall in the breeze, and many strong young trees rise up around it, it alone is honored.

Note that, unlike Caesar, who incinerates everyone in his way, Pompey gives rise to LIFE around him, maintaining a natural balance with young saplings—permitting young Romans to have opportunity to grow, and maybe even surpass him one day, and continue the Roman system. Note too the ominous point that while Pompey once had “strong roots,” they are gone—it is only the “sheer fixed mass” of his achievements that sustain him. And trees, obviously, can be set ablaze by lightning.

Despite this promising beginning, Lucan’s Pompey lacks the energy that characterizes Caesar. While this is fitting in some ways—Pompey did lose after all—it is ahistorical. It is also not in keeping with Lucan’s efforts to make Pompey the secondary hero of the poem.

Throughout the book, Lucan presents Pompey as resigned to his fate. Before the battle of Pharsalus, in Civil War as in reality, Pompey engages Caesar against his will: “[Pompey] groaned, sensing the gods’ tricks, that the fates were contrary to his purpose.” Pompey’s passiveness makes almost all of his passages a snoozefest, especially if they follow ones that feature Caesar. Lucan’s frequent paeans to Pompey’s supposed stoic virtues don’t help matters. Even his death scene—involving a surprise beheading in full view of his wife—doesn’t rate.

Pompey’s boringness might be due to the fact that Lucan’s depiction of him is ahistorical. Pompey—known by the cognomen “Magnus,” or “the Great”—had a record of achievement and military success unmatched among his contemporaries. He, not Caesar, publicly associated himself with and venerated Alexander. Stoic detachment wasn’t his thing—a bon vivant, Pompey built the first theatre in Rome, which Cato criticized for its ostentation. Lucan and his readers would have known all of these things, both through writings on Pompey’s character and older relatives who would have personally known him.

The point of the above is not to chastise Lucan for departing from historical sources. The writer is supposed to take liberties that the historian can’t. But it may explain why Pompey is uncompelling. Lucan’s vision of him is so against type that it doesn’t work.

By contrast, Cato is an interesting character—in the two sections where he is present. Apart from an absurd didactic passage in Book II, where Cato visits Brutus to explain the need to preserve the commonwealth, Cato only appears in Book IX, with his troops in Africa. His leadership abilities—Lucan’s Cato, like the real one, does not ride, but marches alongside his troops—are impressive. Cato is also the only character with a rhetorical ability that rivals Caesar. When some of his troops make to desert, Lucan has Cato give a barnburner that parallels Caesar’s speech to the erstwhile mutineers:

“Go in safety! You deserve for Caesar to grant you life, having never been beaten down in battle or under siege. Wicked slaves! After your former master [Pompey] has met his fate, you’re running to his heir. Why not aim at earning greater things than mere life or pardon? Abduct the wretched wife of Magnus—a daughter of Metellus—take Pompey’s sons to sea with you, outdo Ptolemy’s gift! My head too—whoever shows my face to that vile tyrant will gain no small reward! That band of men will know by the price of my neck that following my standards was well worth it. Come on, then! Reap the bounty on a grander murder. But mere desertion, that’s a coward’s crime.”

Despite the power of the above, Cato’s near absence from the poem is a big problem—especially as Lucan intends him to be the hero of it. It’s unfair to beat up Lucan over this, as he probably intended for the poem to have two additional books. With that, Civil War would have had 12 books—like the Aeneid—and might have ended with Cato’s suicide in Utica. Given that Lucan had clear ability to write a compelling character in Caesar, Lucan’s Cato, in a completed Civil War, might have proved an equally powerful foil.

Catonian Moralizing

While Cato isn’t a large presence in Civil War, his views on Rome and Roman character are one of the main themes of the work. For lack of a better term, I’ll refer to these beliefs as “Catonian Moralizing.”

Catonian Moralizing was popularized by Cato’s ancestor, Cato the Elder, who lived from 234 – 149 BC. In his long political career, which coincided with Rome’s suppression of Carthage and transformation from regional to global power, the elder Cato stressed the need for Romans, of all classes, but especially the senatorial elite, to retain the austere and militaristic qualities of their ancestors. Frugality, military training, farming, writing Latin, and practice of traditional religious rites were encouraged. Profligacy, theatre, exotic foods, speaking Greek, and worship of faddish foreign deities were not. In the political sphere, Cato the Elder’s approach viewed permanent imperial expansion as a corrupting influence. While Rome’s enemies had to be eliminated—Cato the Elder was famous for ending every speech with “And furthermore, Carthage must be destroyed”—foreign lands offered opportunities for wealth and decadence that had to be managed by a prudent and virtuous senatorial elite.

It’s no accident that the elder Cato’s appeal to Rome’s ancestral values coincided with Rome’s acquisition of new territories and increasing wealth. Moralists all of stripes only have a message when old beliefs, once universal, come in for mockery or scorn — or when those old beliefs are forced to contend with foreign modes and orders.

Lucan engages in Catonian Moralizing throughout Civil War. The poem begins with a condemnation of wealth and luxury, and states that it is one of the causes of the war:

But underneath were the public seeds of war, which always sink a powerful people. For when Fortune imported excessive resources from a world brought low, and morals took a backseat to prosperous times and enemy plunder made luxury persuasive, with no end to gold or houses, former foods famished the craving. Men stole and wore apparel barely fit for their sons’ young wives. The nurse of men, Poverty, fled.

In a wonderful passage, Caesar, abandoning all Roman decency, engages in debauchery in Egypt, lurching from a gluttonous banquet to bed a Greek cum Egyptian queen:

Once [Cleopatra’s] peace was born with [Caesar], bought with monstrous gifts, they consummated their pleasures in such grand affairs with a feast, and Cleopatra rolled out in greatest commotion her own display (not yet exported into Roman life and times) of lavish luxuries.

Lucan’s Catonian Moralizing finds its fullest expression in his lament that Romans are wasting blood and treasure fighting other Romans—dissipating energy that could be used to conquer the world:

Who has possessed the world more widely, or through fate’s successes raced so quickly? Each war gave you nations, every year the Titan Sun watched your advance toward both the poles. Just a small stretch of earth remained in the east, until the night was yours, all day was yours, the heavens would run for you, and all the wandering stars beheld would be Roman. But your fates went backward equal to all your years that lethal day in Emathia. In its blood-soaked light it made India feel no horror at Latin rods, and now no consul stops the Dahae’s wandering and leads them inside walls, then girds himself up to mark out Sarmatian colonies with the plows …

In the end, the Civil War has killed so many actual, old-stock Romans, that Rome is no longer Rome, but a foreign city, filled with foreign peoples:

Rome is packed, but not with citizens, stuffed with the scum of the world we’ve given her up to disaster, so that now in such a bloated body a civil war could not be waged!

The above has an ominous resonance for the modern United States. Made great by the qualities of its native, old-stock population, it is actively facilitating the mass migration of foreigners who lack those qualities.

But Catonian Moralizing, like all moralizing, is ultimately a crutch. Lucan failed to recognize that the thing he wanted above all—Roman world empire—was the ultimate cause of civil strife. The new provinces, divorced from Roman custom and law, and inhabited by non-Romans, provided the senatorial elite with opportunities for wealth and glory on a scale unimaginable to prior generations. The Republican system, which promoted spirited competition among its elites, could not accommodate this excess. The benefits of an empire are not possible without its cost. Let us hope our story does not end as Rome’s.

I read the Penguin Classics translation by Matthew Fox. It was published in 2012 and has a good introduction, section breaks, and explanatory notes. If you can read Latin (I can’t anymore), the Loeb edition, translated by JD Duff in 1928, is also worth checking out.

Lucan’s life is recorded by both Suetonius (in a very short biography) and Tacitus (who mentions him in the Annals).

Very nice, thank you!

This is a lovely and very interesting post, and well written. Great job!