The hardest part about blogging is the lack of externally imposed deadlines. If you’re a writer, those types of deadlines are your best friend. They provide motivation and focus, especially when backed by a paycheck—or the threat of losing your job. In absence of external pressure to crank out a post, all that’s left is internal diligence, a quality in which the writer (very much including yours truly) may be lacking.

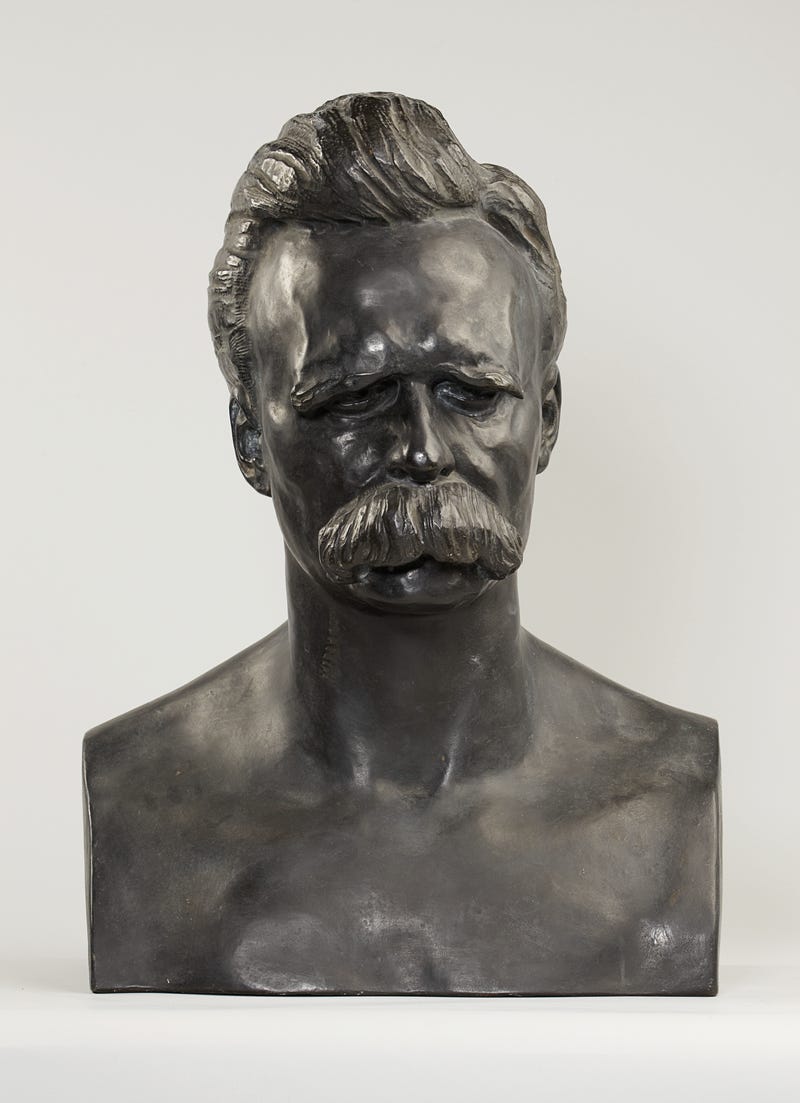

One writer, however, had internal diligence in spades—and made it the subject of his most famous work. In The Protestant Ethic and the “Spirit” of Capitalism, Max Weber provided a controversial theory for the economic dynamism of Northern European countries. In the process, he helped invent a new discipline: sociology. I’ve been threatening to write a post on Weber for months. But to the disappointment of my forbearers, and maybe even Weber himself, I’ve lacked the discipline to do so. But NO LONGER!

To sum up The Protestant Ethic in a paragraph, Weber argued that the spectacular economic success of Britain, America, and the Netherlands from the 1700s onward was the result of Protestant doctrine. While capitalism had always existed, the Protestant concept of predestination infused it with new energy. Protestant believers engaged in business to accumulate, rather than spend, wealth—the accumulation of capital being a sign of God’s favor, and the refusal to spend it displaying discipline and self-denial of worldly pleasures. They invested their accumulated capital in other, new ventures. At scale, this process created explosive growth and economic vitality throughout the Protestant world.

Below are my observations on The Protestant Ethic, as well as Weber’s famous lecture Politics as a Vocation. I can’t speak German, so I read the Penguin Classics translation1 of The Protestant Ethic—published in 2002, the first English translation since Talcott Parsons’ in 1930!—and the Hackett edition of The Vocation Lectures.2 I liked both, and appreciated the translators’ intro and explanatory notes to The Protestant Ethic. The latter were especially helpful because I have no background in sociology. So some of my observations may be disastrously wrong. If you have thoughts about my thoughts, please like or share this post, or leave a comment if the mood strikes you!

Grand Theories

Being charitable, Weber is considered a founder of sociology because The Protestant Ethic didn’t fit neatly into existing disciplines. Being mean spirited, Weber is considered a founder of sociology because historians and economists debunked The Protestant Ethic’s arguments and refused to label Weber as one of their own. Throughout the essay, Weber makes sweeping generalizations and claims about group behavior—which aren’t necessarily supported by historical evidence or economic data.

The problems begin with the title. If capitalism is rooted in Protestantism, how does Weber explain the many Catholic entrepreneurs of his own time, or throughout history? (Note that the word “entrepreneur” comes from French—the language of the first daughter of the (Catholic) Church.)

As an example of this plot hole, take banking—the essence of capitalist activity. In its modern form, it was invented by northern Italians in the 1200 and 1300s. These bankers were Catholics. Ditto for the members of the Hanseatic League and the people of England and the Low Countries, who developed sophisticated trading and financial networks—all before the Reformation. The existence of these networks, and business enthusiasm and (at least nominal) Catholicism of the men who created them, would seem to complicate Weber’s thesis that capitalism, in general, is bound up with and finds its purest expression in Protestantism.

Weber was of course too bright not to anticipate this criticism. These Catholic merchants, he argues, developed the form of capitalist activity, but lacked its spirit. Instead of being “capitalist” they were “traditionalist”:

Of course, the capitalist enterprise is the only possible form in which to operate a business such as a bank, a wholesale export business, a sizeable retail store, or finally, the large-scale putting out of goods manufactured in home industries. Nevertheless, they can all be run in a strictly traditionalist spirt. Indeed, it is not possible for the business of the big banks of issue to be run in any other way. Overseas trade has for whole periods of history been organized on the strictly traditionalist basis of monopolies and quotas.3

Weber furthers this argument by describing the operations of German textile manufacturers before the late 1700s, which he says were leisurely—“office hours were relatively short—perhaps five or six per day, occasionally considerably fewer.” Moreover, “visits to clients, if they occurred at all, were infrequent,” and owners cultivated an “unhurried lifestyle” marked by non-interest in maximizing profits, and more interest in “prolonged daily visits to the club, as well as perhaps a glass of wine in the evening with a circle of friends.” As such:

[The business] was in every respect a “capitalist” form of organization: the entrepreneurs were engaged purely in commerce; the use of capital stocks in the conduct of business was essential; viewed objectively, the economic process was capitalist in form. But it was traditionalist economy if one looks at the spirit which inspired the entrepreneurs: the traditional way of life, level of profit, and amount of work; the traditional tyle of running the business and of relations with workers; the essentially traditional clientele; the traditional manner of obtaining clients and sales. These things dominated the operation of the business and underlay the “ethic” of this circle of entrepreneurs.4

There’s a lot to unpack here. The distinction between a capitalist “form” (a business organization) and capitalist “spirit” (the power and drive of the people that run it) makes sense. And I sort of get Weber’s point about a “traditional” economic model—i.e., business owners who are content with making enough for a comfortable existence, but not fussed about maximizing profits—and how that might differ from a modern business.

But there were almost certainly Catholic merchants—before and after the Reformation—who used capitalist forms (the banks, the League, the guilds), yet had capitalist spirit, too. Said another way, they had ambitions far greater than the “just enough” existence provided by the “traditionalist” model Weber describes. Think of the Medici, or the men of the Venetian Great Council. Their existence and ventures might indicate that, far from being the exclusive product of Protestantism, the origins of the capitalist “spirit” lie much deeper in history, be it in Christianity writ large, or in the immutable characteristics of European peoples. Explaining this possibility away with a microstudy on the German textile industry doesn’t cut it.

Nonetheless, the above is an example of a “good” generalization—something that isn’t right in all its particulars, but is thought provoking and may be stumbling toward a big truth. But Weber also engages in “bad generalization”—sweeping claims that aren’t accurate. His potted history of English and American party development, which takes up more than a few pages in Politics as a Vocation, is a case in point. British party organization became highly professionalized in the 1830s, not the 1880s. That professionalization was instituted by Peel—the epitome of an uncharismatic (in both Weber’s and the dictionary’s sense) leader—not the charismatic Gladstone. Weber’s claim that “party organization was quite loose” until 1824 in the United States would be surprising to John Adams and Thomas Jefferson. These unforced errors poison Weber’s relationship with his reader. If Weber is wrong—in a big way!—about these things, it leads the reader to question his other analyses and conclusions.

But I shouldn’t beat up on Weber too much. Not being all right, or being all wrong, are reasons for a writer to avoid making sweeping claims. But modern writers have taken this truism too far. Hyper-specialists who are afraid of being wrong will produce timid, boring scholarship. The reason Weber is still relevant and worth reading is because he was courageous—he had a big idea that had some basis in fact. In expressing it, Weber swung for the fences. A more measured Protestant Ethic or Politics as a Vocation may have been more accurate. But that accuracy would have made the works less interesting, less readable, and less enduring.

The Heroic Protestant

As noted above, Weber places great emphasis on Predestination as a key motivator of the capitalist “spirit.” Put crudely, the idea of Predestination is that God, being omniscient, knows, at the moment of your conception, where you’re going. While this seems very grim—why try at anything if your name is put down for Hell the minute you’re born?—it actually is just the opposite.

Men, unlike God, are imperfect and ignorant. They have no knowledge of who is destined to go where. So they look for SIGNS of God’s favor in their daily lives. Worldly success—wealth—and the good works that wealth enables, indicate that the prosperous and generous man has been saved:

Totally unsuited though good works are to serve as a means of attaining salvation—for even the elect remain creatures, and everything they do falls infinitely far short of God’s demands—they are indispensable as signs of election. . . . This means, however fundamentally, that God helps those who help themselves, in other words, the Calvinist “creates” his salvation himself (as it is sometimes expressed)—more correctly: creates the certainty of salvation.5

But the wealthy man’s wealth is always tenuous. Money is hard to earn, and even harder to keep. Doing so requires constant work, and prudent investment determined by sober decision making. While losing money is unpleasant, it could be catastrophic for someone who believes in Predestination. If wealth is a sign of God’s favor, losing it could mean that favor is lost—and result in eternal damnation.

This belief transforms work and investment—the mechanisms that allow for the maintenance of wealth—from mere drudgery into something urgent and ceaseless. Because these activities are done in the service of God, to demonstrate election, they are also HOLY. Weber refers to this ennobling of work as “labor in a calling.” Maintaining the signs of one’s election is a constant, never-ending struggle:

It further means that what [the Calvinist] creates cannot consist, as in Catholicism, in a gradual storing up of meritorious individual achievements; instead, it consists in a form of systematic self-examination which is constantly faced with the question: elect or reprobate?6

Two important things spring from this belief—which, as Weber points out, is a system, or methodology, that imbues the men who are processed by that system with certain traits. Most apparent, it makes the acquisition of wealth, and investment in new endeavors to create more wealth, virtuous:

If we may sum up what has been said so far, then, innerwordly Protestant asceticism works with all its force against the uninhibited enjoyment of possessions; it discourages consumption, especially the consumption of luxuries. Conversely, it has the effect of liberating the acquisition of wealth from the inhibitions of traditionalist ethics; it breaks the fetters on the striving for gain by not only legalizing it, but (in the sense described) seeing it as directly willed by God. The fight against the lusts of the flesh and the desire to cling to outward possessions, as not only the Puritans but also the great apologist of Quakerism, Barclay, expressly testify, is not a fight against wealth and profit, but against the temptations associated with them.7

Note that everything we’ve discussed—ceaseless work, self-denial of worldly pleasures, orientation toward the future—can only be achieved by mentally resilient and highly disciplined men. Weber astutely notes that one other feature of Protestant doctrine—disdain for monks and the supposed uselessness of monasticism—had turned a cohort of men with just these qualities loose on an unexpecting world:

Luther was the first to do away with [monasticism]—not as some kind of a “developmental tendency,” but first as a result of his own personal experience, and then after being pressed further by the political system—and Calvinism simply followed on from him. A dam was thus built to prevent asceticism flowing out of secular everyday life, and the way was open for those passionately serious, reflective types of men, who had hitherto provided the finest representatives of monasticism, to pursue ascetic ideals within secular occupations.8

If this sounds exciting, that’s because it is. The WILL of these powerful men, previously confined to the monastic life, will now be used to achieve great things in the secular world:

Christian asceticism, which was originally a flight from the world into solitude, had already once dominated the world on behalf of the Church from the monastery, by renouncing the world. In doing this, however, it had, on the whole, left the natural, spontaneous character of secular everyday life unaffected. Now it would enter the market place of life, slamming the doors of the monastery behind it, and set about permeating precisely this secular everyday life with its methodical approach, turning it toward a rational life in the world, but neither of this world nor for it.9

The Protestant man—far from being a parsimonious and sanctimonious bore—will exert his drive to overcome every obstacle to salvation, and use the accumulation of wealth as a tool in this process. By association, Weber has made capitalism, and the capitalist, HEROIC.

“English Hebraism”

Weber observes that Protestant asceticism, and constant control and self-denial, are buttressed by an obsessive relationship with the Bible, particularly the Old Testament. Protestant clerics and laymen are constant Bible readers and subject it to rigorous textual analysis—about which they then argue among themselves. This combination of an ascetic and legalistic approach to Christianity leads Weber to make an amusing comparison between the Puritans and another group of people who enjoy legalism and textual debate:

So if the tone of English Puritanism is defined as “English Hebraism” . . . this is, rightly understood, quite an accurate definition. However, it is only accurate if applied to the Judaism that emerged under the influence of many centuries of the legalistic and Talmudic training, not the Palestinian Judaism of the period when the Old Testament writings were being produced. The mood of ancient Judaism, which was, on the whole, inclined to the uninhibited appreciation of life as such, is rather far removed from the specific character of Puritanism.10

The Nietzschean Turn

Weber notes that the most enthusiastic devotees of Protestant belief, and best exemplars of the character traits adherence to it produces, are a middling sort:

Wherever the power of the Puritan philosophy of life extended, it always benefited the tendency toward a middle class, economically rational conduct of life, of which it was the most significant and only consistent support.11

With regard to England, this was certainly true: the wealthiest Englishmen were unlikely to be Puritans or members of other dissenting sects. Instead, the non-conforming churches (Puritans, Baptists, Methodists) were made up of people on the make—poor-ish, or vaguely comfortable, but certainly not wealthy.

The POWER of Protestant belief, and the qualities it inculcated, changed all that very quickly. Protestants not only got rich, but their exertions on behalf of their faith caused their ancillary beliefs—devotion to work as a calling, use of capitalism as a mechanism for displaying divine favor—to triumph and be adopted as organizing principles throughout the Anglophone countries and European continent.

All this raises an important question. What happens to the Protestant ethic when Protestants not only get rich, but when their worldview runs the world? Weber’s answer is that it still exists, but becomes unmoored from its religious anchors:

[Puritanism and Methodism], whose significance for economic development lay primarily in the ascetic education they provided, only developed their full economic effect after the pinnacle of purely religious enthusiasm had been left behind, the frenzied search for the kingdom of God was beginning to dissolve into sober virtue in the pursuit of the calling, and the religious roots were beginning to die and give way to utilitarian earthly concerns.12

In other words, the prime exemplar of Protestantism is no longer the heroic, diverted monk described above, who deployed asceticism and the capitalist form to find God. Instead, it is the parsimonious, friendly, but ultimately boring churchgoer who is a “pillar of the community.” There’s nothing wrong with this person—and, as Weber notes, he still focuses on the accumulation of wealth, and possesses some of the character traits necessary to do so. But his end, ultimately, is not God, but the accumulation of wealth itself. Said another way, the child or grandchild of the heroic Protestant is still processed through and maintains the form of Protestant belief—and its most useful vehicle, capitalism—but the spirit is gone:

The Puritans wanted to be men of the calling—we , on the other hand, must be. . . .

As ascetism began to change the world and endeavored to exercise its influence over it, the outward goods of this world gained increasingly and finally inescapable power over men, as never before in history. Today its spirit has fled from this shell—whether for all time, who knows? Certainly victorious capitalism has no further need for this support now that it rests on the foundation of the machine. . . . Where “doing ones’s job” cannot be directly linked to the highest spiritual and cultural values . . . the individual today usually makes no attempt to find any meaning in it. Where capitalism is at its most unbridled, in the United States, the pursuit of wealth, divested of its metaphysical significance, today tends to be associated with purely elemental passions, which at times virtually turn it into a sporting contest.13

The departure of God from human affairs . . . form without spirit . . . alienation. Does this sound familiar? Weber ends The Protestant Ethic with a big wink toward the other German scholar from whom he might be cribbing:

No one yet knows who will live in that shell in the future. Perhaps new prophets will emerge, or powerful old ideas and ideals will be reborn at the end of this monstrous development. Or perhaps—if neither of these occurs—“Chinese” ossification, dressed up with a kind of desperate self-importance, will set in. Then, however, it might truly be said of the “last men” in this cultural development: “specialists without spirit, hedonists without a heart, these nonentities imagine they have attained a state of mankind never before reached.”14

This is a very NIETZSCHEAN view of the future. It’s not very comforting. The phrase “desperate self-importance” describes the worthies of our time with disturbing accuracy. But Weber overlooks that “Chinese” ossification, the emergence of “new prophets, and rebirth of “powerful old ideas” can occur simultaneously, and compete with one another. Let’s hope the right weltgeist wins.

Max Weber, The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism and Other Writings, trans. Peter Baehr and Gordon C. Wells (New York: Penguin, 2002). All quotes are from this edition, and all italics are the translators’.

Max Weber, The Vocation Lectures, trans. Rodney Livingstone, ed. David Owen and Tracy B. Strong (Indianapolis: Hackett, 2004).

TPE, p 20.

TPE, p 21.

TPE, p 79.

Ibid.

TPE, pp 115 - 116.

TPE, pp 82 - 83.

TPE, pp 104 - 105.

TPE, p 112.

TPE, p 117.

TPE, p 118.

TPE, p 121.

Ibid.

Very strong post, Myopic! Clearly written and fun to read. I have The Protestant Ethic on my bookshelf to read, but it seems like you summed it up nicely here...

Excellent piece which somehow popped up in my feed this afternoon. Thoroughly enjoyed your short synopsis of Weber‘s primary work. I had to think of the Swabian (German) billionaire and businessman Adolf Merkle who lived a meticulously Calvinistic life and whose fundamentalist Protestant views informed both his life and death. He committed suicide in Jan 2009 after a financial speculation against VW stock using short positions and options went spectacularly pear-shaped when VW shares were subject to a bear squeeze. The subsequent losses forced him to liquidate the businesses he had spent his entire life building up and, taking this failure as the inverse of God‘s favour and suspecting that at his age he would never be able to regain God‘s favour (ie his previous level of wealth) he took his own life by stepping in front of a train close to his home. He was 74.

I have long suspected that the real driver of the Protestant economic miracle is to be found in the embrace of financial engineering and sophisticated accounting techniques rather than anything else. Jakob Fugger („Der Reiche“) made his fortune applying banking, accounting and trade financing innovations back to Germany and engaging in „money business“ at a time when good Christians (Catholics) regarded any business that was not directly related to real things (trade, handwork, building, agriculture) as Jewish and hateful. The new breed of Protestants freed from these constraints and allowed to work in areas and own property prohibited to Jews, found their wealth creation opportunities legion.